The US is crushing its own Middle Eastern policy with foolish tactical maneuvers. In Syria and Pakistan, the US is launching strikes to try to solve some of its cross-border problems, killing insurgent leaders and trying to create an atmosphere of fear for insurgents across the border--the US is trying to convince them that 3 miles across the border is no longer a safe zone where they can operate freely.

But the short-sightedness of these operations is frustrating. In Pakistan, anti-American sentiment is high and growing. Any hope for NATO-Pakistani military collaboration against the Taliban (particularly now, as Pakistan finally launches an assault against militants in its northwest) has been crushed. The US is going to be sticking around a very long time in Afghanistan, whether we like it or not. When its biggest problems are in Pakistan, it must either work with the Pakistanis or send the entire army in--but a halfway policy is foolish; it neither gains much military advantage, nor does it foster collaboration that would be critical to victory. If we were collaborating, we could make airstrikes in Pakistani territory with Pakistani ground intelligence--it would be hailed by the government as an effort conductive to stabilizing its regime. But attacks without permission force the government into an anti-US stance, because its sovereignty has been violated repeatedly.

Attacks on Syria are even more foolish. Syria is not a weak state, and its influence matters. The US is right that Syria can't completely control its border, but nor can the US control its own with Mexico. After more than a year of Westernization by Syria, this attack is hurting that process seriously. Syria is likely to be more skeptical of such Westernization, due to a lack of trust in Western powers. The US can't afford to radicalize Syria by violating its sovereignty--and if it does, it should at least make some PR efforts by apologizing.

In particular, while the US is negotiating its stay beyond December with Iraq, it does not help itself by showing Iraqis that the US will use Iraq as a staging ground for attacks on its neighbors. The US is not just justifying current anti-American sentiment, but bringing loyalty to question among Iraqi parliament members that are thinking of voting for the security pact.

Life is going to get a lot tougher for the US in the Middle East unless it quickly tries to revere the trend in perceptions.

Defense, National Security, and Foreign Policy Analysis in the Dynamic System of International Relations and Diplomacy

Tuesday, October 28, 2008

Sunday, October 26, 2008

The Great Middle East Limbo

The US Election is zooming in quickly, but even after Senator Obama wins (let's face it), he won't have the authority to do his own peace-brokering quiet yet. Arabs abroad love him, and would probably give him an opportunity to try his hand at mediation.

But right now, there's a more limiting factor that will keep him sidelined for even the first month or two of his presidency. Tzipi Livni, the head of the Kadima party and their candidate for Prime Minister, has failed to create a coalition government in Israel's Knesset (parliament). She's citing "political blackmail" by potential coalition partners; unable to reign in their allegedly unreasonable demands (especially because some of them stand to gain in an early election), she moved to an election.

Her decision to have an election likely means there just wasn't another option. Kadima does not want to delay the peace process with Palestine, nor does it want to open the door for Netanyahu's Likud party to gain power again. Likud is polling well, and if they won, would probably expand (not contract) Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Gaza, and probably even in the Golan heights. Peace talks with Syria and the Palestinian Authority would break down. This is not an illegitimate or summarily bad position for Israel to have, but it will unquestionably frustrate the EU and US, who have been be ating their heads against brick walls to make this happen--and who saw, just before the fall of Olmert, a glimmer of hope in the open-mindedness of Palestine's Abbas and Syria's Assad to shift West. Before Olmert's fall, a fair number of international political analysts were predicting a surprisingly happy Middle East by 2011. That optimism has all but vanished.

ating their heads against brick walls to make this happen--and who saw, just before the fall of Olmert, a glimmer of hope in the open-mindedness of Palestine's Abbas and Syria's Assad to shift West. Before Olmert's fall, a fair number of international political analysts were predicting a surprisingly happy Middle East by 2011. That optimism has all but vanished.

If Kadima manages to win the election, it will have been after serious delays--delays in which a coup may take down Assad, or an assassination might take down Abbas. The Israeli election will probably occur in February, putting at least 4 more months of delay on talks. It's something that has lots of people nervous.

That said, Likud brings up some serious points to the discussion table. Israel is in a position where, after 60 short years, it has learned many times over that land-for-peace often does not work in the Arab world. If the Palestinian Authority cannot control its own people (hint: it can't), then summarily pulling out from PA territory would greatly increase the operations capabilities of the more Hamas-leaning Palestinians. Would extremism go away quickly in the PA? Certainly not. And concessions in the light of terror attacks in Israel might send the message that continued terror attacks will eventually lead to more concessions--or more thoroughly disrupt the Israeli government. Until all but a few Palestinians can either be A) convinced that Israel is there to stay, or B) suppressed by a strong Palestinian government, Israel puts its citizens at serious risk by giving up the PA territories.

The Golan Heights are less critically disastrous, but similar. In theory, if Israel gave the Golan Heights back to Syria, Syria would stop funding Hamas and Hezbollah operations in Israel, greatly increasing Israel's security. Some have mentioned that the Golan Heights are militarily advantageous, and they are--but not by much. The Israeli army is far superior to Syria's, and Syria will never again get the help of I raq, Jordan, or Egypt if it tried to pick a fight with the Israelis. Syria would be crushed in any head-to-head battle with the Israelis. Besides--Blue Helmets would probably line the heights for a fair while after the handover, to keep it demilitarized.

raq, Jordan, or Egypt if it tried to pick a fight with the Israelis. Syria would be crushed in any head-to-head battle with the Israelis. Besides--Blue Helmets would probably line the heights for a fair while after the handover, to keep it demilitarized.

But those Blue Helmets might be Israel's bane in such a handover deal. If the Syrians don't hold to their promises--and keep funding anti-Israeli terrorist organizations--then the Israelis can't do much about it. Referring to a recent post of mine, Israel has a lot of power with de facto control over the Heights, and if it agreed to a new status quo, it would face a heavy burden to overturn it--especially if UN troops would be hurt in the process. Syria might be able to do whatever it wants when Israel's bargaining chips are gone--especially if Israel couldn't afford the political cost of taking them back.

The situation's sticky. But it's about to get even stickier--hopelessly so--if Israeli elections get messy. Lame-duck and incoming presidents alike are going to be frustrated and disheartened. But it's just another day in the life of the Middle East peace process.

But right now, there's a more limiting factor that will keep him sidelined for even the first month or two of his presidency. Tzipi Livni, the head of the Kadima party and their candidate for Prime Minister, has failed to create a coalition government in Israel's Knesset (parliament). She's citing "political blackmail" by potential coalition partners; unable to reign in their allegedly unreasonable demands (especially because some of them stand to gain in an early election), she moved to an election.

Her decision to have an election likely means there just wasn't another option. Kadima does not want to delay the peace process with Palestine, nor does it want to open the door for Netanyahu's Likud party to gain power again. Likud is polling well, and if they won, would probably expand (not contract) Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Gaza, and probably even in the Golan heights. Peace talks with Syria and the Palestinian Authority would break down. This is not an illegitimate or summarily bad position for Israel to have, but it will unquestionably frustrate the EU and US, who have been be

ating their heads against brick walls to make this happen--and who saw, just before the fall of Olmert, a glimmer of hope in the open-mindedness of Palestine's Abbas and Syria's Assad to shift West. Before Olmert's fall, a fair number of international political analysts were predicting a surprisingly happy Middle East by 2011. That optimism has all but vanished.

ating their heads against brick walls to make this happen--and who saw, just before the fall of Olmert, a glimmer of hope in the open-mindedness of Palestine's Abbas and Syria's Assad to shift West. Before Olmert's fall, a fair number of international political analysts were predicting a surprisingly happy Middle East by 2011. That optimism has all but vanished.If Kadima manages to win the election, it will have been after serious delays--delays in which a coup may take down Assad, or an assassination might take down Abbas. The Israeli election will probably occur in February, putting at least 4 more months of delay on talks. It's something that has lots of people nervous.

That said, Likud brings up some serious points to the discussion table. Israel is in a position where, after 60 short years, it has learned many times over that land-for-peace often does not work in the Arab world. If the Palestinian Authority cannot control its own people (hint: it can't), then summarily pulling out from PA territory would greatly increase the operations capabilities of the more Hamas-leaning Palestinians. Would extremism go away quickly in the PA? Certainly not. And concessions in the light of terror attacks in Israel might send the message that continued terror attacks will eventually lead to more concessions--or more thoroughly disrupt the Israeli government. Until all but a few Palestinians can either be A) convinced that Israel is there to stay, or B) suppressed by a strong Palestinian government, Israel puts its citizens at serious risk by giving up the PA territories.

The Golan Heights are less critically disastrous, but similar. In theory, if Israel gave the Golan Heights back to Syria, Syria would stop funding Hamas and Hezbollah operations in Israel, greatly increasing Israel's security. Some have mentioned that the Golan Heights are militarily advantageous, and they are--but not by much. The Israeli army is far superior to Syria's, and Syria will never again get the help of I

raq, Jordan, or Egypt if it tried to pick a fight with the Israelis. Syria would be crushed in any head-to-head battle with the Israelis. Besides--Blue Helmets would probably line the heights for a fair while after the handover, to keep it demilitarized.

raq, Jordan, or Egypt if it tried to pick a fight with the Israelis. Syria would be crushed in any head-to-head battle with the Israelis. Besides--Blue Helmets would probably line the heights for a fair while after the handover, to keep it demilitarized.But those Blue Helmets might be Israel's bane in such a handover deal. If the Syrians don't hold to their promises--and keep funding anti-Israeli terrorist organizations--then the Israelis can't do much about it. Referring to a recent post of mine, Israel has a lot of power with de facto control over the Heights, and if it agreed to a new status quo, it would face a heavy burden to overturn it--especially if UN troops would be hurt in the process. Syria might be able to do whatever it wants when Israel's bargaining chips are gone--especially if Israel couldn't afford the political cost of taking them back.

The situation's sticky. But it's about to get even stickier--hopelessly so--if Israeli elections get messy. Lame-duck and incoming presidents alike are going to be frustrated and disheartened. But it's just another day in the life of the Middle East peace process.

Labels:

defense,

Election,

foreign policy,

International Relations,

israel,

Kadima,

Likud,

national security,

Obama,

palestine,

peace talks,

Syria,

US

Tuesday, October 21, 2008

Saudi Arabia Cleans House

991 Saudis have been simultaneously indicted for terrorism (technically, "acts of rebellion" or "acts of war" against the state) over the past 5 years by the Riyadh government. Recall first that many Saudis were involved in the 9/11 attacks, and that foreigners in Saudi Arabia have been attacked with bothersome frequency by Wahhabi terrorists. Americans mostly perceive the Saud royal family of spending more time bathing in petrodollars than doing anything to help, despite being an alleged "friend" of the Bush regime.

991 Saudis have been simultaneously indicted for terrorism (technically, "acts of rebellion" or "acts of war" against the state) over the past 5 years by the Riyadh government. Recall first that many Saudis were involved in the 9/11 attacks, and that foreigners in Saudi Arabia have been attacked with bothersome frequency by Wahhabi terrorists. Americans mostly perceive the Saud royal family of spending more time bathing in petrodollars than doing anything to help, despite being an alleged "friend" of the Bush regime. It's a bit different than that. The Saudi government doesn't really like the Wahhabis or Al-Qaeda or other fundamentalist nutjob terrorists, despite their own fundamentalist leanings, and despite

their support of very questionable Sunni militants in Iraq. Al-Qaeda and the Wahhabis don't really like Saudi royal rule, and often make trouble for the population. Terrorism in Saudi Arabia has killed 160 citizens and wounded hundreds more.

their support of very questionable Sunni militants in Iraq. Al-Qaeda and the Wahhabis don't really like Saudi royal rule, and often make trouble for the population. Terrorism in Saudi Arabia has killed 160 citizens and wounded hundreds more. Why hadn't the Sauds dealt with it yet? Part of it is that they have a surprisingly tenuous grasp on power. They're not about to fall, but they don't have much in the way of representative legitimacy, and Wahhabism is pretty darn powerful in Saudi Arabia. The Saud government certainly wanted to avoid an all-out war with its own Wahhab people; it was happier to leave them alone.

But why now? Well, the unhappiness by the Sauds with the Wahhabis didn't go away--the Saud family was not thrilled to have them around. The huge number of simultaneous indictments indicates that this was a "one swift stroke" kind of motion--the Saud government is making a power grab. It's a risky move--if it's not intimidating enough, Wahhabis may rebel en masse--creating a messy internal war (much like the one that Pakistan is trying to fight now). But if the show of force is sufficient--if it can disrupt, demoralize, and decapitate the Al-Qaeda and Wahhabi organization, then they've got a good shot at nearly permanently weakening their extremist groups.

The timing may also have to do with Iraq--they may have decided that the civil war is over, and they no longer need to stay friendly with their own Sunni insurgents/extremists to keep funding the militias in Iraq. The Iraqi factor may have been holding them back for the last 5 years, and may finally be over.

Labels:

Al-Qaeda,

defense,

Iraq,

national security,

Saud,

Saudi Arabia,

terrorism

Sunday, October 19, 2008

The Iraq Snag

After months of tough negotiating over a pact that Bush thought would be pretty easy, it looked like a deal would come out a few days ago. The Iraqi executive branch had agreed to a 2011 withdrawal timeline with the ability to renegotiate and extend the timeline every year.

After months of tough negotiating over a pact that Bush thought would be pretty easy, it looked like a deal would come out a few days ago. The Iraqi executive branch had agreed to a 2011 withdrawal timeline with the ability to renegotiate and extend the timeline every year.The announcement of the basics of the pact by the Iraqi government led to a wave of protests--mostly by Al-Sadr supporters--against the pact, complete with American flag-burning and other anti-American slogans. Soon after, hardcore extremist sections of the Iraqi parliament declared they'd vote the bill down without new concessions--an elimination of the ability to renegotiate, and less legal protection for US troops in Iraq (from Iraqi law). The bill won't pass without their support. The US government will have to negotiate again.

It is unclear to me whether the Shiites are going to stop here or not. The US must have a pact by December, and the Shiites know that. Many of them (including the influential Al-Sadr) would be happy to see the Americans go. But if they said that they'd be unwilling to vote for any sort of security pact with the US, they would likely appear too extreme to work with the Iraqi government. They may simply stall until December comes. They may also be stalling until they get a very-temporary pact, one that extends the US stay for 6 months while negotiations continue. Why? If the pact is signed on time, it will be before the new US president. But with all signs pointing to a win by Mr. Obama, who is well-known in Iraq for his anti-war voting and rhetoric, Iraqi Shiites may try to game the pact such that President Obama is the final negotiator on the US side in order to maximize their concessions. They may also be trying to use brinksmanship on the pact, and push it until December before they agree to it, hoping to milk the current US administration for concessions as they desperately try to get something reasonable signed before the deadline passes and the administration loses power.

It's also possible this is the extent of Shiite expectations. It's tough to tell.

There's one good sign in all of this: much of the rhetoric by lawmakers and marchers is very pro-Iraqi. They are emphasizing their desire for sovereignty and national freedom, which will ultimately be a uniting factor. Hopefully, a big party will happen all over Iraq when the last US troop goes home, complete with Iraqi flags flying out windows. Nationalism is key to the success of a nation-building effort, and key to heal the wounds of a tough civil war. The US, which has done a wonderful job of absorbing blame in the past few decades, can stand to be the big-bad-wolf figure that creates an Iraqi nationalism that keeps the country together during its formative infant-democratic years.

Labels:

Bush,

defense,

Election,

foreign policy,

International Relations,

Iraq,

national security,

Obama,

Security Pact,

Treaty,

US

Saturday, October 18, 2008

The Iraq Endgame

The Iraq Endgame is on. General Petraeus has masterfully used the last 2 years to turn Iraq around from a seemingly-hopeless civil war to a functional--if highly flawed--Middle Eastern state that will soon be ready to control its own security. Mr. Petraeus has also managed to largely immunize his plan from the politics of the US Presidential Election and the US-Iraqi Security Pact, as we can see in the first figure, below.

Figure One: Iraqi Provincial Control

Figure One: Iraqi Provincial Control

A few very interesting observations should be noted about this poll. First, Anbar is one of the most responsive provinces to the question of confidence in the Government of Iraq (GoI). This kind of poll undermines serious concerns about Anbar citizens being able to accept government hegemony. Basrah has very little confidence, but this is largely due to the power of the Al-Sadr militia there--supporters of the militia are necessarily anti-government, and non-supporters feel largely unsafe, and lack confidence in the government's ability to keep Al-Sadr in check. The very red results in Ninawah and Salad al-Din are more difficult to interpret. I will have to look into it.

A few very interesting observations should be noted about this poll. First, Anbar is one of the most responsive provinces to the question of confidence in the Government of Iraq (GoI). This kind of poll undermines serious concerns about Anbar citizens being able to accept government hegemony. Basrah has very little confidence, but this is largely due to the power of the Al-Sadr militia there--supporters of the militia are necessarily anti-government, and non-supporters feel largely unsafe, and lack confidence in the government's ability to keep Al-Sadr in check. The very red results in Ninawah and Salad al-Din are more difficult to interpret. I will have to look into it.

Average daily electrical power remains low. Here, I am not sure why the US is not able to use its many hundreds of billions of spending to build some oil-run power plants. It seems a rather simple solution. Any insight from my readers would be appreciated. Here we see the once-infamous security incident trends graph. Particularly low here are small arms attacks--mortar, gunfire, RPGs, etc. This indicates that the Iraqi insurgents have lost their ability to operate openly--they cannot simply patrol their blocks with arms, waiting for Coalition or ISF troops to jump. Anti-government attacks remain somewhat stubborn--this is strange largely due to the fact that Sunnis have largely stopped attacking the government (think Sons of Iraq) and the Shiite extremist groups have a lot of power in the government currently. Either these attacks are by Al-Qaeda and other fundamentalists (which is very possible given the high number of IED and other bomb attacks/removals remaining in this chart), or Shiite gangs in Basrah have stopped fighting each other and have tried to take control of the city instead.

Here we see the once-infamous security incident trends graph. Particularly low here are small arms attacks--mortar, gunfire, RPGs, etc. This indicates that the Iraqi insurgents have lost their ability to operate openly--they cannot simply patrol their blocks with arms, waiting for Coalition or ISF troops to jump. Anti-government attacks remain somewhat stubborn--this is strange largely due to the fact that Sunnis have largely stopped attacking the government (think Sons of Iraq) and the Shiite extremist groups have a lot of power in the government currently. Either these attacks are by Al-Qaeda and other fundamentalists (which is very possible given the high number of IED and other bomb attacks/removals remaining in this chart), or Shiite gangs in Basrah have stopped fighting each other and have tried to take control of the city instead.

This trend graph is one of the less dramatic--the green line is Iraqi Security Forces deaths, and it's not particularly heartening. 100 or so ISF troops are still killed per month, and that number has been stubborn for months. It's an indication that the dramatic decrease in US deaths is due in large part to the fact that US troops have taken a back seat in security operations. US troop deaths cannot be used as a direct proxy for peace in Iraq. On the other hand, it means that the ISF is growing increasingly competent--if they are taking a larger and larger role in Iraq and their death toll is not increasing, then they are definitionally becoming safer per capita or per operation. Expect to see this number drop a few months after the full handover is complete (probably May). This is probably the most heartening graph in the set. Ethnosectarian deaths are 2 orders of magnitude lower today than they were in December 2006, at their peak. The civil war is just plain over, and the ISF now needs to concentrate on fundamentalist militant groups and Shiite gangs. This is a sigh of relief for the ISF. During the civil war, protecting one group meant giving it a military advantage against the other--there were no clear "victims," and the government was the enemy of most of its citizens--and thus it undermined its own support. But as it eliminates al-Qaeda, confidence in its ability to protect and serve will grow. When that confidence is high enough, it will have the political capital to pressure Al-Sadr and the Shiite gangs to disarm, or finish them once and for all. The Iraqi government is not going to tolerate having its own Hezbollah-style groups running around its southern regions.

This is probably the most heartening graph in the set. Ethnosectarian deaths are 2 orders of magnitude lower today than they were in December 2006, at their peak. The civil war is just plain over, and the ISF now needs to concentrate on fundamentalist militant groups and Shiite gangs. This is a sigh of relief for the ISF. During the civil war, protecting one group meant giving it a military advantage against the other--there were no clear "victims," and the government was the enemy of most of its citizens--and thus it undermined its own support. But as it eliminates al-Qaeda, confidence in its ability to protect and serve will grow. When that confidence is high enough, it will have the political capital to pressure Al-Sadr and the Shiite gangs to disarm, or finish them once and for all. The Iraqi government is not going to tolerate having its own Hezbollah-style groups running around its southern regions.

Perhaps the most important sign of security success is civilian deaths; reducing civilian deaths (and pain and displacement, etc) is the primary job of the ISF, and deaths are probably an excellent proxy for all the bad stuff. Current monthly civilian deaths are 1/7 their peak, and are not as stubborn as the ISF death numbers--that is, they have declined int he last 6 months. This means that the ISF is improving the security of its citizens as it takes over, while simultaneously not losing more men per month.

Perhaps the most important sign of security success is civilian deaths; reducing civilian deaths (and pain and displacement, etc) is the primary job of the ISF, and deaths are probably an excellent proxy for all the bad stuff. Current monthly civilian deaths are 1/7 their peak, and are not as stubborn as the ISF death numbers--that is, they have declined int he last 6 months. This means that the ISF is improving the security of its citizens as it takes over, while simultaneously not losing more men per month.

We should note that confidence lags security significantly--and why shouldn't it? When one has lived in civil war and terror for years, one is not going to jump on reports of a quiet month and decide that everything is okay. By the time the new president is in office, though, confidence in the government's ability to keep Iraqis safe is likely to be much higher. When that happens, Iraq will be ready to run itself--it is still a highly flawed country, but when people begin to feel safe, they can return to normalcy, and the government can more easily address the non-security needs of its nation. This is the endgame. We must now see how cheaply and quickly we can take our leave.

This picture has come a very long way from the mess that Petraeus inherited in February 07, and is right on track with his March 2008 predictions, except for Ninawah (pushed back 1 month) and Baghdad (pushed back a full 6 months). By the time the new president is in office, all provinces except for Baghdad will be under full Iraqi security control, with only minimal US support given. Petraeus is ready for even a hasty withdrawal, or some other form of unfavorable Iraq security pact.

In Iraqi polls, the number of people that feel safe in their neighborhood has shot up dramatically. This confidence is key to finally being able to report to authorities the locations and goings-on of local militias and gangs, which undermine the security of those outside one's neighborhood (which is why those poll number are so very low). If one feels very safe in his own neighborhood, he knows he'll receive protection if he is an informant, or if he stops funding the militias. Without funding or anonymity, the militias will be increasingly easy to track down and break up.

A few very interesting observations should be noted about this poll. First, Anbar is one of the most responsive provinces to the question of confidence in the Government of Iraq (GoI). This kind of poll undermines serious concerns about Anbar citizens being able to accept government hegemony. Basrah has very little confidence, but this is largely due to the power of the Al-Sadr militia there--supporters of the militia are necessarily anti-government, and non-supporters feel largely unsafe, and lack confidence in the government's ability to keep Al-Sadr in check. The very red results in Ninawah and Salad al-Din are more difficult to interpret. I will have to look into it.

A few very interesting observations should be noted about this poll. First, Anbar is one of the most responsive provinces to the question of confidence in the Government of Iraq (GoI). This kind of poll undermines serious concerns about Anbar citizens being able to accept government hegemony. Basrah has very little confidence, but this is largely due to the power of the Al-Sadr militia there--supporters of the militia are necessarily anti-government, and non-supporters feel largely unsafe, and lack confidence in the government's ability to keep Al-Sadr in check. The very red results in Ninawah and Salad al-Din are more difficult to interpret. I will have to look into it.

Average daily electrical power remains low. Here, I am not sure why the US is not able to use its many hundreds of billions of spending to build some oil-run power plants. It seems a rather simple solution. Any insight from my readers would be appreciated.

Here we see the once-infamous security incident trends graph. Particularly low here are small arms attacks--mortar, gunfire, RPGs, etc. This indicates that the Iraqi insurgents have lost their ability to operate openly--they cannot simply patrol their blocks with arms, waiting for Coalition or ISF troops to jump. Anti-government attacks remain somewhat stubborn--this is strange largely due to the fact that Sunnis have largely stopped attacking the government (think Sons of Iraq) and the Shiite extremist groups have a lot of power in the government currently. Either these attacks are by Al-Qaeda and other fundamentalists (which is very possible given the high number of IED and other bomb attacks/removals remaining in this chart), or Shiite gangs in Basrah have stopped fighting each other and have tried to take control of the city instead.

Here we see the once-infamous security incident trends graph. Particularly low here are small arms attacks--mortar, gunfire, RPGs, etc. This indicates that the Iraqi insurgents have lost their ability to operate openly--they cannot simply patrol their blocks with arms, waiting for Coalition or ISF troops to jump. Anti-government attacks remain somewhat stubborn--this is strange largely due to the fact that Sunnis have largely stopped attacking the government (think Sons of Iraq) and the Shiite extremist groups have a lot of power in the government currently. Either these attacks are by Al-Qaeda and other fundamentalists (which is very possible given the high number of IED and other bomb attacks/removals remaining in this chart), or Shiite gangs in Basrah have stopped fighting each other and have tried to take control of the city instead.

This trend graph is one of the less dramatic--the green line is Iraqi Security Forces deaths, and it's not particularly heartening. 100 or so ISF troops are still killed per month, and that number has been stubborn for months. It's an indication that the dramatic decrease in US deaths is due in large part to the fact that US troops have taken a back seat in security operations. US troop deaths cannot be used as a direct proxy for peace in Iraq. On the other hand, it means that the ISF is growing increasingly competent--if they are taking a larger and larger role in Iraq and their death toll is not increasing, then they are definitionally becoming safer per capita or per operation. Expect to see this number drop a few months after the full handover is complete (probably May).

This is probably the most heartening graph in the set. Ethnosectarian deaths are 2 orders of magnitude lower today than they were in December 2006, at their peak. The civil war is just plain over, and the ISF now needs to concentrate on fundamentalist militant groups and Shiite gangs. This is a sigh of relief for the ISF. During the civil war, protecting one group meant giving it a military advantage against the other--there were no clear "victims," and the government was the enemy of most of its citizens--and thus it undermined its own support. But as it eliminates al-Qaeda, confidence in its ability to protect and serve will grow. When that confidence is high enough, it will have the political capital to pressure Al-Sadr and the Shiite gangs to disarm, or finish them once and for all. The Iraqi government is not going to tolerate having its own Hezbollah-style groups running around its southern regions.

This is probably the most heartening graph in the set. Ethnosectarian deaths are 2 orders of magnitude lower today than they were in December 2006, at their peak. The civil war is just plain over, and the ISF now needs to concentrate on fundamentalist militant groups and Shiite gangs. This is a sigh of relief for the ISF. During the civil war, protecting one group meant giving it a military advantage against the other--there were no clear "victims," and the government was the enemy of most of its citizens--and thus it undermined its own support. But as it eliminates al-Qaeda, confidence in its ability to protect and serve will grow. When that confidence is high enough, it will have the political capital to pressure Al-Sadr and the Shiite gangs to disarm, or finish them once and for all. The Iraqi government is not going to tolerate having its own Hezbollah-style groups running around its southern regions. Perhaps the most important sign of security success is civilian deaths; reducing civilian deaths (and pain and displacement, etc) is the primary job of the ISF, and deaths are probably an excellent proxy for all the bad stuff. Current monthly civilian deaths are 1/7 their peak, and are not as stubborn as the ISF death numbers--that is, they have declined int he last 6 months. This means that the ISF is improving the security of its citizens as it takes over, while simultaneously not losing more men per month.

Perhaps the most important sign of security success is civilian deaths; reducing civilian deaths (and pain and displacement, etc) is the primary job of the ISF, and deaths are probably an excellent proxy for all the bad stuff. Current monthly civilian deaths are 1/7 their peak, and are not as stubborn as the ISF death numbers--that is, they have declined int he last 6 months. This means that the ISF is improving the security of its citizens as it takes over, while simultaneously not losing more men per month.We should note that confidence lags security significantly--and why shouldn't it? When one has lived in civil war and terror for years, one is not going to jump on reports of a quiet month and decide that everything is okay. By the time the new president is in office, though, confidence in the government's ability to keep Iraqis safe is likely to be much higher. When that happens, Iraq will be ready to run itself--it is still a highly flawed country, but when people begin to feel safe, they can return to normalcy, and the government can more easily address the non-security needs of its nation. This is the endgame. We must now see how cheaply and quickly we can take our leave.

Labels:

Al-Qaeda,

defense,

foreign policy,

International Relations,

Iraq,

Iraqi Security,

Militia,

national security,

Petraeus,

Shiite,

Sunni,

surge,

US,

War in Iraq

Thursday, October 16, 2008

The Power of the De Facto

The de facto can be a very powerful force in international politics--when things are a certain way, it is usually the burden of the party that wants to change it to justify that change, even if we all agree that the status quo is a bad idea. For some folks, it's a really bad deal. Others take advantage of it. Today, we'll review some of the interesting current status quo kinks in the world.

1) Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The status quo of South Ossetia and Abkhazia were tenuously against the Russians' favor one year ago--they had peacekeepers in both regions, but they were recognized as Georgian, despite the Georgians not having administrative control. But the Russians performed a masterful swap--their war was a shock, certainly, but one that they (probably) had the political capital to bear, largely due to European forgiveness of the US invasion of Iraq. Russia is insisting on the same forgiveness, particularly given the plausibility of the story that Georgia provoked them by moving (themselves unprovoked) into South Ossetia. The Europeans and Americans were not happy, but had very little to yell about. With weak justification for their anger, the EU and US mostly agreed that they'd been duped, and lost. Now, Russian de facto presence in--and support of--the breakaway states is the new status quo that the EU and US will have to fight to overcome... if they care enough.

peacekeepers in both regions, but they were recognized as Georgian, despite the Georgians not having administrative control. But the Russians performed a masterful swap--their war was a shock, certainly, but one that they (probably) had the political capital to bear, largely due to European forgiveness of the US invasion of Iraq. Russia is insisting on the same forgiveness, particularly given the plausibility of the story that Georgia provoked them by moving (themselves unprovoked) into South Ossetia. The Europeans and Americans were not happy, but had very little to yell about. With weak justification for their anger, the EU and US mostly agreed that they'd been duped, and lost. Now, Russian de facto presence in--and support of--the breakaway states is the new status quo that the EU and US will have to fight to overcome... if they care enough.

2) Kurdistan. It's tough to dispute that the Kurds were left the short end of the stick in the post-WWI division of the Middle East; they were the largest nationality without their own state. After decades of fighting, the Turks, Iraqis, and Iranians--for all their mutual irritation--are working together to keep them suppressed. Nobody in the Middle East wants to give them independence. The fact that they don't have independence creates enough inertia that they simply won't.

largest nationality without their own state. After decades of fighting, the Turks, Iraqis, and Iranians--for all their mutual irritation--are working together to keep them suppressed. Nobody in the Middle East wants to give them independence. The fact that they don't have independence creates enough inertia that they simply won't.

3) US Attacks on Pakistan. The power of de facto has allowed the US to slowly creep up the boldness of its attacks in Pakistan--now, they're just lobbing missiles into Waziristan to take out Talibani leadership. While this is certainly the militarily sound strategy, it's risky--it is alienating a weak--but once dedicated--ally in the GWoT. And while the Pakistani leadership will continue to protest--they must, if they are to be re-elected--but ultimately tolerate it. What else can they do?

4) Taiwan. An oldie but a goodie. While the US (and every other darn country in the world) agree that there is One China, not Two Chinas, the international community would not tolerate any force on the part of the Chinese to take Taiwan back. The de facto independence of Taiwan is China's burden to overcome, even though nobody officially supports formal independence. The fact that it is the way it is continues to be compelling, even though no government argues that it's the way things should be.

When something looks odd or wrong in international politics, think whether some odd de facto force is present. It may be quite revealing.

1) Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The status quo of South Ossetia and Abkhazia were tenuously against the Russians' favor one year ago--they had

peacekeepers in both regions, but they were recognized as Georgian, despite the Georgians not having administrative control. But the Russians performed a masterful swap--their war was a shock, certainly, but one that they (probably) had the political capital to bear, largely due to European forgiveness of the US invasion of Iraq. Russia is insisting on the same forgiveness, particularly given the plausibility of the story that Georgia provoked them by moving (themselves unprovoked) into South Ossetia. The Europeans and Americans were not happy, but had very little to yell about. With weak justification for their anger, the EU and US mostly agreed that they'd been duped, and lost. Now, Russian de facto presence in--and support of--the breakaway states is the new status quo that the EU and US will have to fight to overcome... if they care enough.

peacekeepers in both regions, but they were recognized as Georgian, despite the Georgians not having administrative control. But the Russians performed a masterful swap--their war was a shock, certainly, but one that they (probably) had the political capital to bear, largely due to European forgiveness of the US invasion of Iraq. Russia is insisting on the same forgiveness, particularly given the plausibility of the story that Georgia provoked them by moving (themselves unprovoked) into South Ossetia. The Europeans and Americans were not happy, but had very little to yell about. With weak justification for their anger, the EU and US mostly agreed that they'd been duped, and lost. Now, Russian de facto presence in--and support of--the breakaway states is the new status quo that the EU and US will have to fight to overcome... if they care enough.2) Kurdistan. It's tough to dispute that the Kurds were left the short end of the stick in the post-WWI division of the Middle East; they were the

largest nationality without their own state. After decades of fighting, the Turks, Iraqis, and Iranians--for all their mutual irritation--are working together to keep them suppressed. Nobody in the Middle East wants to give them independence. The fact that they don't have independence creates enough inertia that they simply won't.

largest nationality without their own state. After decades of fighting, the Turks, Iraqis, and Iranians--for all their mutual irritation--are working together to keep them suppressed. Nobody in the Middle East wants to give them independence. The fact that they don't have independence creates enough inertia that they simply won't.3) US Attacks on Pakistan. The power of de facto has allowed the US to slowly creep up the boldness of its attacks in Pakistan--now, they're just lobbing missiles into Waziristan to take out Talibani leadership. While this is certainly the militarily sound strategy, it's risky--it is alienating a weak--but once dedicated--ally in the GWoT. And while the Pakistani leadership will continue to protest--they must, if they are to be re-elected--but ultimately tolerate it. What else can they do?

4) Taiwan. An oldie but a goodie. While the US (and every other darn country in the world) agree that there is One China, not Two Chinas, the international community would not tolerate any force on the part of the Chinese to take Taiwan back. The de facto independence of Taiwan is China's burden to overcome, even though nobody officially supports formal independence. The fact that it is the way it is continues to be compelling, even though no government argues that it's the way things should be.

When something looks odd or wrong in international politics, think whether some odd de facto force is present. It may be quite revealing.

Labels:

De Facto,

defense,

foreign policy,

Georgia,

International Relations,

Iran,

Iraq,

Kurdistan,

Pakistan,

Russia,

South Ossetia,

Taiwan,

Turkey,

US

Wednesday, October 15, 2008

Succumbing to European Pressure, Russia Stops Bullying Georgia, Resumes Killing Own Citizens

Russia began its withdrawals from Georgia a few days ahead of each deadline, according to the Sarkozy-brokered ceasefire deal, and has tried to go to the negotiating table with Georgia. They haven't made it to the same negotiating room yet--but that's okay, they tried. Russia has seen how bad PR can really hurt its export-heavy economy, and has pushed its PR pretty hard to try and return to appearing relatively innocuous.

Russia began its withdrawals from Georgia a few days ahead of each deadline, according to the Sarkozy-brokered ceasefire deal, and has tried to go to the negotiating table with Georgia. They haven't made it to the same negotiating room yet--but that's okay, they tried. Russia has seen how bad PR can really hurt its export-heavy economy, and has pushed its PR pretty hard to try and return to appearing relatively innocuous.But the Russian government is yet to learn that attacking its own people might not be great for Public Relations, either. Years after the James Bond-esque Litvinenko ordeal, as well as mysterious bullet holes in the heads of anti-government writers, the Kremlin is being accused of attempted murder once again.

French police are launching an investigation after finding toxic pellets in Karinna Moskalenko's car. Moskalenko is investigating the murder of Anna Politkovskaya, an anti-Kremlin activist (one that ended up with a bunch of holes in her head).

Should all these accusations pan out, then the Russian government is getting desperate. It's not only killing anti-government activists, but also anyone investigating the killings of these activists. Putin probably doesn't have control of the courts--else the Kremlin would unlikely continue its murder streak. But again, this is speculation.

Putin climbed the ranks of the KGB before becoming Moscow's head-of-everything, and his strongest allies are certainly in the security business. It's very little surprise that, when armed with one of the biggest hammers in Eurasia, every problem looks like a nail. Expect the hammer to keep falling.

Become a Foggofwar Follower

If you have a Blogspot account, click on the "Follow This Blog" link to become a follower. I think it just reminds you when you log in that you're a follower, so you're more likely to click it. I just want a lot of faces there, because more approval will legitimize me as a person.

Just kidding. Do it anyway.

Just kidding. Do it anyway.

Monday, October 13, 2008

Iraqi Muslim Sectarian Groups Put Aside Infighting, Kill Other Religions Instead

A lot of progress has been made in the past few years in trying to get the Iraqi sectarian groups to get along. More and more, the Shiites and Sunnis are grumbling their way towards working for joint development and governance. The passing of the crucial election laws means there will be a flawed--but quite improved--representation in government for Sunnis.

A lot of progress has been made in the past few years in trying to get the Iraqi sectarian groups to get along. More and more, the Shiites and Sunnis are grumbling their way towards working for joint development and governance. The passing of the crucial election laws means there will be a flawed--but quite improved--representation in government for Sunnis. But amid these improvements, a new sort of religious targeting has occurred. Christians, particularly in Mosul, have been attacked and killed, driven out, or have simply fled. Mosul,

which was once known for heterogeneity and tolerance, is now swarming with anti-Christian gangs, prompting the government to send 1000 extra security personnel.

which was once known for heterogeneity and tolerance, is now swarming with anti-Christian gangs, prompting the government to send 1000 extra security personnel.There is some speculation as to what has caused this sudden ethnic cleansing. It might be because of Christian protests--local election laws in Niniveh have taken away Christian quotas in parliament, and Christians have taken to the streets on Mosul and Baghdad over it. Such protests may be angering some Muslim minorities, who are looking to consolidate as many seats this coming October as possible (for example, Sunni Kurds). Until elections actually happen, there may be perverse power plays, intimidation, bribery, and all sorts of corruption to try to game the system into giving each group a political advantage.

And therefore! I believe that this is the very reason that provincial security handovers are on a long pause, despite the fact that security is good in a few of these regions (Wasit, Babil, Ta'mim): until the election, American forces want to be as present as is reasonable, and really make sure security is strong enough to prevent intimidation and other forms of disenfranchisement. When the election is over, the crisis will recede--violence against minorities will get Iraqis in more trouble than the payoff they can expect might balance. Therefore, the US is waiting until December to handover.

If Iraq can get this situation under control until the election, the Christians might be safe--but on the other hand, there may be angry reprisals by gangs or extremist sections of political groups that are angry at a raw deal--and looking for a scapegoat. It is easier for extremist Muslims to justify violence against Christians than other Muslims, and probably a bit easier to get away with, given the questionable reliability of some of the Iraqi Security Forces. But if the government can show that it's willing to pull out all the stops to protect its minorities, it will earn a lot of much-needed security credit.

Labels:

Christians,

defense,

Iraq,

Iraqi Security,

Mosul,

Muslims,

national security

Monday, October 6, 2008

Biden Reaffirms Dem Ticket Has No Idea How Islam Works

By asserting, repeating, and defending that the Sunnis and Shiites have just been killing each other off for the past 700 years. Good thing we've got such an experienced foreign policy expert on the Democrat ticket.

By asserting, repeating, and defending that the Sunnis and Shiites have just been killing each other off for the past 700 years. Good thing we've got such an experienced foreign policy expert on the Democrat ticket.Turns out the Sunnis and Shiites, while not always fans of each other, have mostly gotten along for most of the last 700 years. Under the Ottoman empire, they were united against outsiders--despite not having strong or brutal leadership out of Turkey. Their primary disagreement comes in whether it is more important to follow the current religious leadership and keep societal cohesion, or to be right--the Shiites think that they have a responsibility to overthrow or at least disobey the religious leadership if they are corrupt or incorrect, where Sunnis think that is a mandate for a widespread undermining of Islamic society. That's the base of it.

They're not different religions. They're not even different like the Catholics and Protestants. All it takes to be a Muslim is the declaration that Allah is the one true god and Mohammed is his prophet. Boom, done. Islamic states don't officially differentiate between Sunnis and Shiites, even if one is a majority--they recognize that Muslim is Muslim. Even in Sharia societies, the different approaches of Sunni and Shi'a Islam lead to surprisingly similar results. Sunnis and Shiites in Iraq got along relatively well, even before Saddam took power.

Part of the problem is that before the First World War, nation-states didn't exist in the Middle East--there were various Islamic empires, and provinces, but Islam was the organizing force in society, rather than political states. The creation of the nation-state in the Middle East made things more complicated, but most states chose

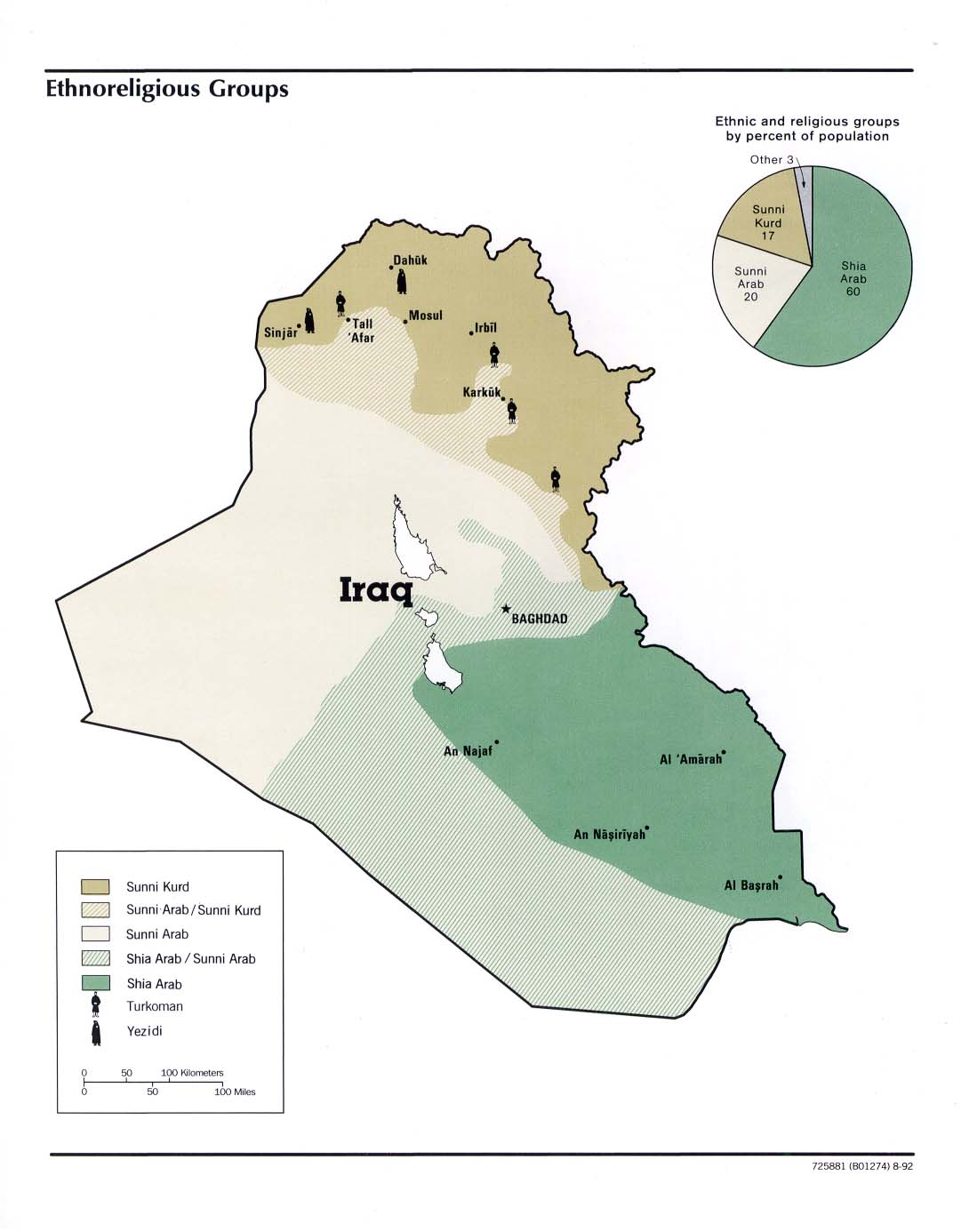

whether or not to incorporate Islam (with Turkey being the only major state that didn't) into the government. But the growing strength of the nation-state meant that being a minority stuck in a bunch of arbitrary boundaries with a majority sometimes meant that the state denied you adequate protection, opportunity, or access, which led to contention. Therefore, Sunni-Shiite disparate identity led to security dilemmas. Iraq, the state with the smallest majority of either sect (in this case, Shiites hold a mere 60%) in the Middle East, has the strongest prerogative for that kind of security dilemma when the security apparatus of a country disintegrates and future resource-allocation is highly unclear.

whether or not to incorporate Islam (with Turkey being the only major state that didn't) into the government. But the growing strength of the nation-state meant that being a minority stuck in a bunch of arbitrary boundaries with a majority sometimes meant that the state denied you adequate protection, opportunity, or access, which led to contention. Therefore, Sunni-Shiite disparate identity led to security dilemmas. Iraq, the state with the smallest majority of either sect (in this case, Shiites hold a mere 60%) in the Middle East, has the strongest prerogative for that kind of security dilemma when the security apparatus of a country disintegrates and future resource-allocation is highly unclear. While the Sunni-Shiite sectarian civil war should have been foreseen, that does not mean it had been happening over the past 700 years. Obama may have slipped when he said that it had, but Biden's firm repeating and defending of that position to attack McCain just simply means that he has no idea what he's talking about, despite years of experience on the Foreign Relations Committee. Luckily for Biden, being wrong has never stopped him from sticking to his guns before.

Labels:

Biden,

Democratic Party,

Election,

foreign policy,

Iraq,

Islam,

National Identity,

national security,

Obama,

sectarian,

Shiite,

Sunni

The Humbling of China

China in the last few years has gotten some bad publicity from exports: milk, toothpaste, dogfood, Barbie Dolls--all tainted and dangerous in some way. For most of it, one simply has to admit that sometimes things go wrong in the sheer mass of exports that China puts out each year. The milk was the boulder that broke the camel's back--when your government has crafted an export-dependent economy, your international image is critical. 54,000 babies sickened by melanine in milk, and some dead--Western and even wealthy Chinese families don't trust the safety and efficacy of Chinese products. If nobody trusts your products, nobody will buy them.

China in the last few years has gotten some bad publicity from exports: milk, toothpaste, dogfood, Barbie Dolls--all tainted and dangerous in some way. For most of it, one simply has to admit that sometimes things go wrong in the sheer mass of exports that China puts out each year. The milk was the boulder that broke the camel's back--when your government has crafted an export-dependent economy, your international image is critical. 54,000 babies sickened by melanine in milk, and some dead--Western and even wealthy Chinese families don't trust the safety and efficacy of Chinese products. If nobody trusts your products, nobody will buy them. This is very bad news for China. It's brought a very large magnifying glass to the export control machinery in its government--and that glass has found little. The term "crisis in confidence"--being tossed around about US financial markets--is surprisingly relevant here. China is overhauling its entire milk industry and oversight bureaucracy to try and restore confidence in its already-strained exports. With oil prices high and real disposable income down, its ships crossing the pacific aren't making as much money as they used to be. The last thing the Chinese Communist Party--which bases its legitimacy in growth--needs is a recession, and it's willing to do anything it can to try to boost buyer confidence in its products. The Chinese government has rounded up 32 people allegedly involved, and whether or not they are is largely inconsequential--they need a scapegoat, they need to be able to say "we got the bad guys, they're gone now."

But China did something strange. This crisis has been so bad that the Chinese government called its own industry "chaotic." It has admitted something is wrong with the way that its country is currently doing things. This is a rare sort of admission that is the closest thing to an apology one is ever going to get out of the Chinese government. They are clearly embarrassed, and a bit humbled: they are not perfect.

Chinese humbling has to come from within. Strong nationalism means that criticism from without will be met with significant backlash, and will feed such nationalism. Trying to shake one's finger at China is seen as insulting and petty, and won't "socialize" the Chinese government, as the US and the West hope to do. China has to learn from its own mistakes the hard way; it must see the consequences of them.

Personally, I would cite the biggest mistake here as the one in which the Chinese government tried to build an export-dependent economy--when you make exports the backbone of your wealth, then drops in exports lead to disaster. But despite the fact that I think the Chinese reaction is not fully economically optimal, it is a good political sign--the Chinese export economy does indeed require China to keep a good reputation abroad. As long as it does not try to overhaul its entire economy to something more mixed or "independent," it will depend on its reputation to keep a strong economy--and the Party needs a strong economy to maintain its one-party legitimacy. If the economy is good, don't shake things up, they say. But if it's bad... why not?

So the Party will continue behaving in the future. A humble China is a peaceful China, and a peaceful China is a wonderful partner for the future, even if it will disagree with the West.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)