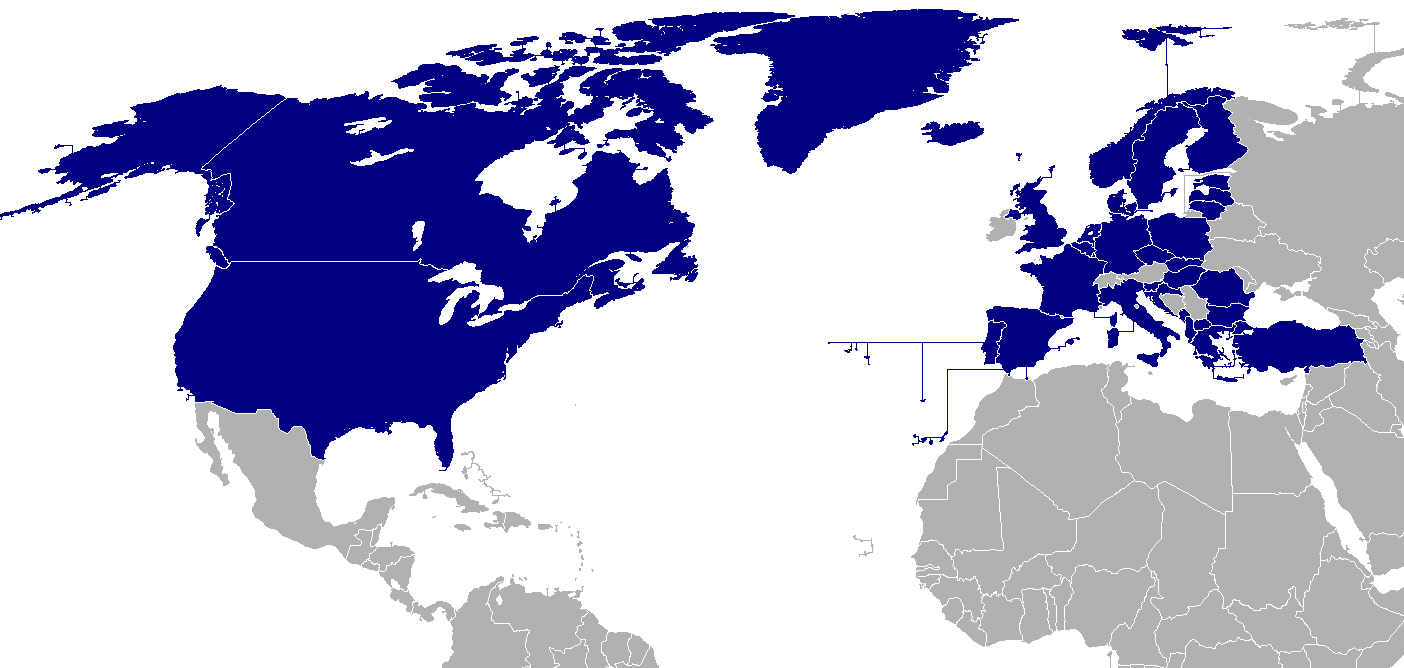

On April 8th and 9th (with lots of pomp and circumstance thanks to the presence of all three presidential candidates, trying to show off for the press), General David Petraeus gave his Great Iraq Update to Senate, discussing progress and future strategy. Released to the public was a

handout that each Senator received, and I humbly present my analysis of some of the better graphics from it.

Because I am a geopolitical wonk, I keep coming back to the Iraq Provincial Security Transition Assessment Map (or Provincial Iraqi Control Map). As we can see, some interesting progress has been made. Half of all Iraqi provinces (9/18) have been handed over, though the handover process stalled after 2007. In July, the third-last Polish-led province of Qasidiyah, as well as the once-restive province of Anbar will be handed over. Anbar's "renaissance" will be completed in July, and the Bush Administration is likely to hold it high as a sign of success in Iraq.

Interestingly, there seems to be no politically-motivated rush on the part of Petraeus to hand over other provinces; six provinces are going to be handed over immediately

after the US 2008 election, if they are handed over on time. Petraeus may have been able to stack some of these provinces in a lump October 2008 handover to try and influence US voters to elect a more pro-occupation candidate like John Mccain, but has opted not to, presumably in favor of a more militarily sensible strategy.

Interestingly, all provinces but Tam'im are scheduled to be fully handed over to Iraqi Provincial Control by the time a new president is sworn into office. In doing so, Petraeus is able to (intentionally or not) preempt any new president's Iraq strategy by sealing the United States Military's fate as a secondary force in Iraq by 2009. The post-handover provinces in Iraq have not all been perfectly peaceful--the recent violence in Basrah has been an embarrassment to the possibly-hasty full UK pullout--but ethno-sectarian violence remains low (despite a small spike), and Al-Qaeda seems to be losing ground. Continued handover, despite March's spike in violence, looks like it will progress smoothly.

The next gorgeous chart here is ethno-sectarian violence in Iraq (this measures only deaths by inter-sect rivalries, rather than Al Qaeda bombings or Al-Sadrite militia spats with the Iraqi Army). As we can see, Iraq has passed its "civil war" stage of 2005-2007, and remains in a state of tough pacification and unification. Whether ethno-sectarian violence remains quite this low after a US drawdown over the summer remains to be seen, but political progress is slowly and painfully being made. More importantly than parliamentary benchmarks, perhaps, is Petraeus-led integration of Iraqi Army and National Police units into communities, mirroring the integration the Petraeus implemented with US troops. Such an integration provides a stable security base (lowering the incentive to support militias for one's street-side security) and also a friendly and helpful grassroots face for the government (increasing civilian support of its continued success). So while critics point to a strikingly slow development of nationwide laws that are meant to bring long-term stability, the ubiquitous-police society developed, especially in Baghdad, is likely to maintain stability in urban centers as the government continues to try and reconcile political differences.

McCain called Baghdad life "more or less normal" in a recent speech, and these graphs are the best evidence we can get to support such a claim. Assuming these graphs are not designed to intentionally mislead, Baghdad now looks more or less like a large American urban center in its ethnic violence density. Nationwide ethno-sectarian deaths remain at about 200 per month, or 2400 per year, which is about 8.2 ethno-sectarian deaths per 100,000 people (the US homicide rate is 5.6 per 100,000 even though this is a pretty poor comparison). Again, this doesn't include suicide bombings or the recent Mahdi-Iraqi Army fighting. On that note:

The MNF Coalition estimates about 300 total civilian deaths last month (12.3 per 100,000 per year), and Iraqi data estimates about 750 total civilian deaths last month (projecting to about 21 per 100,000 pear year); both estimates are higher than political scientists would see as sustainable and acceptable for a stable domestic society.

Finally, the last image is the most promising, if it's accurate. Even if Iraq does not become a fully stable and and pro-American society any time soon, Al-Qaeda remains the United States' enemy number one. To leave Iraq as a safe haven for Al-Qaeda would be a total military failure of the operation, regardless of any other political or military progress in the country. It remains the United States' moral obligation to clean up the mess created in Iraq by its overthrow of the Hussein regime, but it remains the United States' primary security obligation to eliminate Al-Qaeda at all corners, and deny them all possible havens. Progress in eliminating Al-Qaeda in Iraq since the Surge strategy has been stark.

Completing a rooting-out of of Al-Qaeda looks within reach. Continued progress on bringing political reconciliation, military stability, and delivery of daily necessities to the Iraqi people will create a sustainable country in which Al-Qaeda's destabilizing presence will not be tolerated.