Well, looks like I was wrong about the status of the Kurdish regions of Iraq, and also wrong about which province is going to be handed over next.

The Kurdish provinces are under Iraqi Provincial Control (IPC). It's possible that IPC is the very reason the PKK has had a freer reign in the region, but they are starting to talk peaceful resolution, and the Iraqi government has shut down their recruiting offices. If the PKK issue can be resolved, the north will probably return to relative quiet.

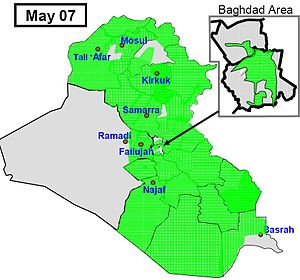

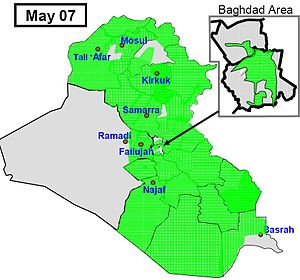

Remember this map is from August, and Karbala has been handed over. That puts us at 8 provinces handed over, and zero "not ready for transition." Compare this to 14 months ago:

One province handed over, and four "in the red," not ready for transition. Furthermore, Iraqi forces are in the lead in many of the provinces partially ready for transition, and US forces are taking an ever-increasing support role in the war:

The green indicates "Iraqi Army Lead." Notice that in 3 or 4 eastern provinces not yet handed over, they are in full lead. According to the

US DoD, Basra is the next province on the list to be handed over-- and they plan to do it by the year's end, making 9 of the 18 Iraqi provinces under full Iraqi control.

Note the change in the rate of handover since the surge:

From Mar 2003 - July 2006 (30 months): 1 province handed over

From August 2006 - Jan 2007 (6 months): 2 additional provinces handed over

From Feb 2007 - Oct 2007 (Surge period, 9 months): 5 additional provinces handed over

From Nov 2007 - Dec 2007 (Projected, 2 months): 1 additional province handed over

Given the violence by province in the first half of the year:

The relative peacefulness of Qadisiyah and Wasit indicates that their transition will come not after a tough putting-down of violence, but after the United States is satisfied with the functionality of the local police force and civil services. They show the potential to be handed over early next year, and Tamim and Babil have shown recent declines in violence that could make them acceptable for handover within months. This leaves the US 5 provinces to concentrate its security operations before domestic pressures bring the troops home:

1) Baghdad. Certainly the most important province in Iraq, I believe Baghdad will be the last to be handed over. Hopefully, the surge will secure Baghdad fast enough (see the first pretty picture in the previous entry) such that post-surge level troops (troop levels will begin to reduce to pre-surge levels in Feb, 2008) can keep the city under control. Baghdad will benefit most from the cascading effect of Iraqi Provincial Control, as more and more US forces in Iraq are likely to move into Baghdad to further pressure insurgent groups. But, if the US is able to hand over most provinces by the end of 2008, the new US president may only have to commit 30,000 or fewer troops in Baghdad to keep Iraq on its feet.

2) Anbar. Anbar has surely shown the most improvement over the last year, due in part to the surge, but mostly to brilliant diplomatic efforts that have brought the tribal leaders of this Sunni-majority province to support the government. Additional provincial attacks charts should illustrate Anbar's improvement well:

Just before the surge, Anbar province was suffering an average of 35 attacks per day.

In the beginning phases of the surge, other provinces showed only some or no improvement, but Anbar had dropped to 25 attacks per day, an almost 30% drop. This was due not to a large insertion of troops, but to a decision by Anbar Sunnis to begin supporting the Iraqi Government. Attacks continue to plummet: notice that in the last Provincial Security Transition Assessment, Anbar, after stubbornly staying in a "not ready for transition" state for more than 4 years, has finally made significant progress towards peace and security, and could soon turn itself from Iraq's biggest trouble spot to a leader role in unification.

3) Salah Ad Din: Home to the infamous Tikirt and Samarrah, it has remained a trouble spot for US forces. The United States must try and spread the pro-government sentiment of the Anbar Sunnis to the Sunnis in Sala Ad Din if it is to calm down. Furthermore, Salah Ad Din suffers from being a relatively large Sunni and Shiite mixing ground, especially in Samarrah. Americans are leading strong efforts to get tribal leaders to sit down and talk in this region, but unfortunately, I don't have up-to-date enough violence-by-province data to tell you whether it's working well or not.

4) Diyalah: A mixing ground of all three major ethno-religious groups of Iraq, Diyalah may be a trouble spot for some time. That said, it has been the second-least-violent of our 5 remaining "trouble" provinces, but the US does not consider the level of violence there to yet be acceptable. This province will be the truest testing ground of coalition reconciliation efforts; that is, given the sheer amount of ethnic mixing, large decreases in violence in Diyalah will truly show that ethnic groups are finally putting aside their differences.

Finally,

5) Ninewah. We don't hear much about Ninewah because, while it is a trouble spot, it has about half the number of attacks on a daily basis than Diyalah. Ninewah is an area of strong Sunni and Kurdish mixing (I think you're seeing a pattern), and contains Mosul, a high-density, high-ethnic-mixing city. Ninewah may well benefit from increased Sunni support-- with Kurds already mostly supporting the Iraqi government, Sunni realignment will likely give the two ethnic groups common ground on which to work, and common goals to work for.

Challenges remain. Al Qaeda in Iraq continues terror attacks against Iraqi civilians, but this may be a sign of leadership failure in the organization. Osama Bin Laden has urged Iraqis to work together to throw the US out, while other elements of Al Qaeda have stubbornly refused to halt terror attacks. As Iraqi tribal groups increasingly turn to crush Al Qaeda, their influence and effectiveness will falter.

Let's talk Turkey: could a Turkish invasion destabilize Iraq? Possibly. But a full-scale invasion is unlikely to happen, and even if military operations do cross the border, fighting between the Turks and Kurds will likely not have much effect on Iraq's 3 biggest trouble spots. The risk here is that either A) the Iraqi government will lose the support of its Kurdish citizens for not protecting them, or B) the Turkish government will see the Iraqi government as ambivalent or hostile to its interests, and Iraq needs all the international (especially neighbor) support it can get. Iraq has asked its neighbors for assistance in solving the matter with strong diplomacy and minimal military operations, and strong US and NATO influence with Turkey is likely to keep them from doing anything rash.

Finally, Iran: is the Iranian government funneling in weapons? Is the Revolutionary Guard conducting operations in Iraq? If so, are these significant? The answers to these are, unfortunately, unclear. But Iran seems to be on the defensive, thanks largely to US and EU sanctions and pressure. The Iranian government is almost certainly looking to expand its power, and certainly wants Iraq as an ally or even a puppet, seeing as Iraq is the only other large, Shiite-majority country in the world. But does Iran have the ability at the moment to expand its empire against the wills of the US and EU? While Russia may be a shaky ally of Iran, its power and influence are slim. If Iran wants to destabilize Iraq enough to force US troops out (as it will have to do before it can think about large-scale imperial efforts), it had better act soon, because trends seem to be in US and Iraqi favor.

Things are looking very good for Iraq at the moment. It seems the favorable trends that the surge has brought will continue through next February. If the US has properly prepared the Iraqi government, police force, and military, then these groups should well be able to take over the administration of security within Iraq, and keep violence to a low enough level that government and business can expand their functionality. If this transition works, the US can start to scale down troop commitments as early as summer of 2008, giving the citizens of the US some much-needed hope and relief, and throwing a wrench in the politics of the 2008 presidential election.